Insects for fun and for real

Location: Russian State Library, Centre of Oriental Literature, Exhibition Hall

Time: 15 May — 14 June 2019

Admission: free with a reader pass

The exhibition Insects for fun and for real was devoted to the traditions and symbolism of insects in Japanese and Chinese ink paintings and prepared by the Artistic Union of Japanese

Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden. China, between 1679 and 1818. Fragment. Photo by Maria Govtvan, RSL

The traditional art of China and Japan is distinguished by a sophisticated aesthetic vision of nature. Each image is filled with hidden meaning and symbolism. Both the artist and the viewer can learn a lesson in beauty and harmony from nature. While admiring ink paintings, it is important to recognise what feelings and emotions are embedded in those images, and even more importantly — to learn to understand them.

In 1788, the Japanese artist Kitagawa Utamaro released an engraving album called the Book of Insects. His teacher Toriyama Sekien wrote in his introduction to this book, «He who wants to paint pictures must first understand the structure of living beings with his heart and then copy it with a brush. … He borrows his sparkle from the brilliant beetle to eclipse the older art, he takes weapons from the grasshopper to fight it, and, like an earthworm, he digs under the basement of an old building. He tries to penetrate the secrets of nature with the sensitivity of a maggot, with fireflies illuminating his path, and he does not stop until he reaches the edge of the web…»

The art section of the exhibition showed the examples of the most common

Butterflies symbolise levity and grace in Japanese culture. They indicate immortality, abundant leisure, joy, and summer. In Chinese paintings, if a butterfly is depicted with a plum, it symbolises longevity and beauty, and if it is depicted with a chrysanthemum, it stands for beauty in old age. Two butterflies in one picture hint at a happily married couple, love and harmony.

A bee is a symbol of hard work, zeal, frugality, and a cosy home. The image of a bee can also indicate a possible promotion. A peony surrounded by bees symbolises a girl in love.

Cricket . The lovely chirping of a beloved children’s fairy tale character is a symbol of home, comfort, and peace. In Chinese art, a cricket symbolises summer, courage, and fighting spirit. In many countries, crickets stand for luck, courage, warmth, and thanks to the fictional Talking Cricket, they might also stand for conscience (or inner voice).

Ladybug is a symbol of good luck.

Grasshopper — in China, it is associated with abundance and large families (with many sons). If it is depicted with a chrysanthemum, it indicates a high rank.

Ant — «a righteous insect», symbolizes hard work, order, virtue, patriotism, and subordination.

In China dragonfly is a symbol for summer and instability. The Japanese have it on their national emblem, as its image resembles what the Japanese islands look like.

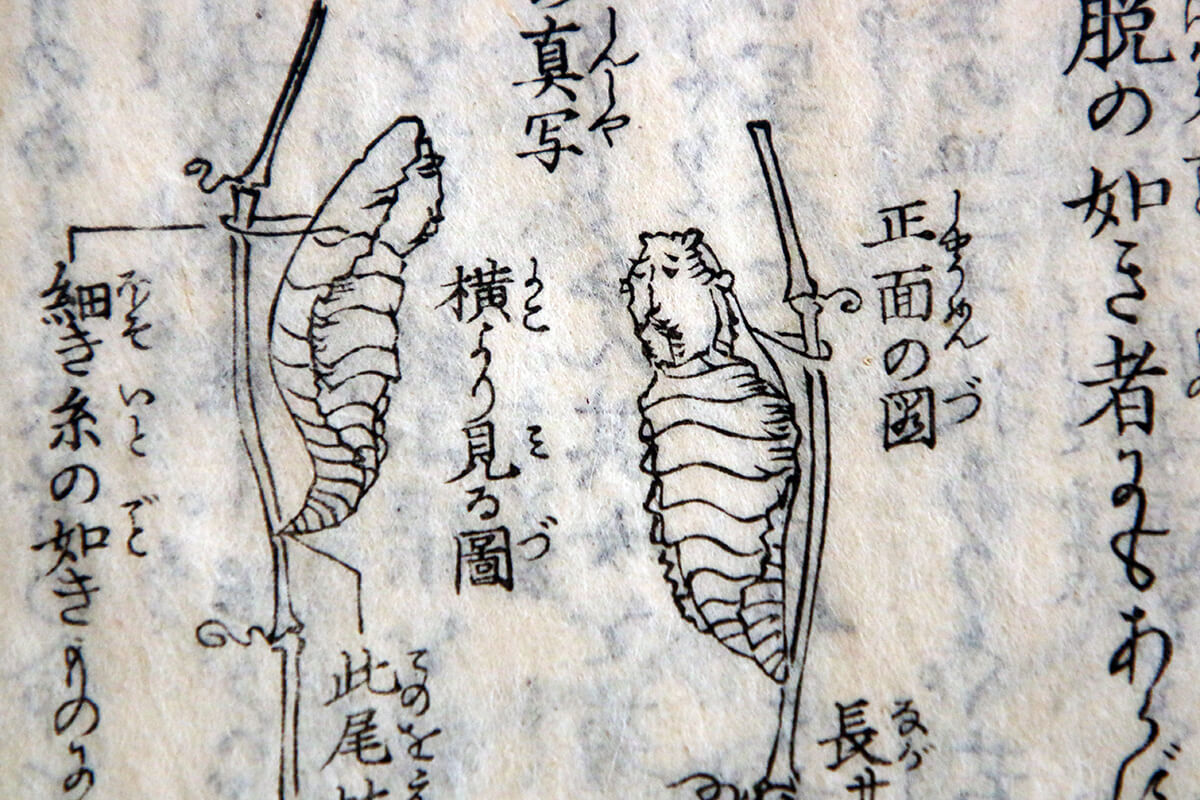

The book section of the exhibition included unique editions with illustrations by Chinese and Japanese artists.

Among them was a classic painting guide, Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden (China, 1679—1771), a remarkable example of Chinese book art. The aim of the Manual was to reveal painting methods and tricks, and serve as a helpful guide to artists. The

The exposition presented two volumes of the Manual, «Flowers and birds» and «Insects».

The exhibition also displayed unique publications with illustrations by the great Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760—1849). His drawings represent a whole era in the history of Japanese art. Manga (Hokusai’s Sketches) is one of the artist’s most important works that he created at the height of fame. Hokusai’s Manga is often called «the encyclopaedia of Japanese life». The exhibition featured several woodcut collections published in Tokyo (Edo) in 1814—1878.

Japanese art was largely represented by 19th century editions with illustrations of engravings by distinguished artists executed in the Flowers and Birds genre. «Pictures of Flowers and Birds» (or

Images in this genre were painted by Kōno Bairei (1844—1895) for the publication of the Bairei hyakuchō gafu published in Tokyo in 1884, as well as by Takizawa Kiyoshi (19th century) for the book of Senryudo gafu published in 1881. Of particular interest is the

In addition, insects and birds often appear in children’s picture books. The exhibition showed a picture book about a sparrow (Suzume), published in Tokyo in 1933 and the tale of Issumboshi, published in Tokyo in 1933.

On 1 June, artist Alla Mikhailovna Solovyova, a member of the board of the Artistic Union of Japanese

Various notes by Akatsuki no Kanenari. 1862. Fragment. Photo by Maria Govtvan, RSL